Last week, Vice President Kamala Harris unveiled a proposal to expand Medicare benefits to cover some long-term care services. Under the “Medicare at Home” initiative, individuals who are unable to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)—such as bathing or preparing meals—without assistance could be eligible for in-home care. The proposal offers up to 20 hours per week of home care services, with cost-sharing for higher-income recipients based on a sliding scale.

If implemented, this would mark the first major expansion of Medicare since the addition of prescription drug benefits in 2003 under George W. Bush’s administration. Moreover, the proposed expansion, could be as impactful—and expensive—as the addition of Medicare Part D.

Currently, the proposal exists as a high-level, two-page fact sheet, leaving critical details undecided, such as the scope of eligibility, benefit limits, and funding mechanisms. It is difficult, therefore to provide an analysis of the merits or feasibility (political and financial) of the proposed policy change. But this is an important (and too often neglected) topic, so let’s give it a shot with what we’ve got.

What Are Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS)?

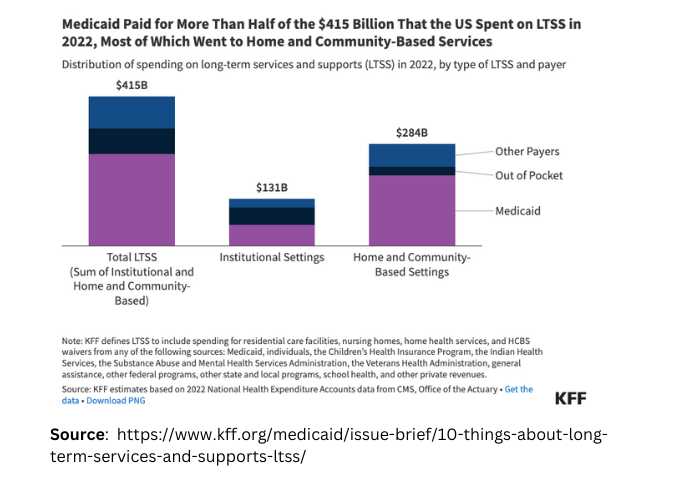

Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) refer to a range of medical and non-medical services needed by individuals who can no longer perform ADLs independently due to aging or disability. LTSS includes everything from personal care, as mentioned in Harris’s plan, to nursing home care and 24-hour home health services. These services can be delivered in facilities (like nursing homes and assisted living centers) or in the community. While long term care is traditionally most closely associated with skilled nursing facility, the majority of these services (~68%) are actually delivered in the home and community, as reflected in the figure below. This reflects the preference for most individuals to remain in their homes as they age as well as the varied services and interventions available in the home and community.

As the population ages and life expectancy increases, the demand for LTSS will grow. Currently, national LTSS expenditures amount to more than $467 billion annually, accounting for more than 13% of U.S. health care spending. That number is only going to increase. More than half (56%) of Americans who live to age 65 will require some form of LTSS, with over 20% of American’s requiring services over a period of at least five years. These services are also expensive. The US Department of Health and Human Services estimates that, on average, an American turning sixty-five in 2022 will incur over $120,000 in long term services over the course of their life. That is a cost which, in the absence of Medicaid (an insurance program for individuals of limited means and the primary payer for LTSS nationally), fails primarily on individuals and families. This doesn’t account for the cost of unpaid caregiving, which is predominantly done by women and is estimated to amount to over $600 billion annually.

It is for this reason that the effort to address the gap in the availability and affordability of long term services and supports is pitched as one part of a package of economic relief plans targeting middle-income families. It is for this reason that Harris’s plan is squarely framed as one part of a package of economic relief plans targeting middle-income families.

Medicare as a Vehicle for Change

Using Medicare as a vehicle to address the costs of long term care is significant in and of itself. The advantage of Medicare expansion is its (virtually) universal application among Americans over age 65. This could alleviate the burden on middle-income families and address the “sandwiched generation”—those caring for both children and aging parents. But just as importantly, the proposal could help accelerate the shift toward value-based care in the long-term care industry by removing a long-standing barrier to value based contracting and collaboration. A primary barrier to value-based care in this sector is the lack of alignment between Medicaid, the primary payer for LTSS, and Medicare. By integrating LTSS under Medicare, Harris’s proposal could incentivize greater coordination between long-term care providers and the broader healthcare system, leading to more proactive and cost-effective care.

What’s Next?

Addressing the gap in long term care affordability, availability, and quality is a topic too long deferred in our national discourse. It is also one that cannot be deferred much longer. However, the big question is whether Harris’s proposal is politically and financially feasible. Any expansion of Medicare benefits requires congressional action—a high hurdle to pass, and increasingly difficult in our current political climate. Moreover, the program’s projected cost is substantial. A Brookings Institution analysis suggests the program could cost $40 billion in its first year, a figure they freely concede is conservative.

Bridging the long-term care gap is going to be expensive. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that up to 14.7 million individuals, or 23% of the Medicare population, would qualify for Harris’s proposed benefit. Harris proposes to fund the expansion through the savings generated through the Medicare Price Negotiation, however this would be insufficient to cover the full cost. The Congressional Budget Office projects that price negotiation will save up $31 billion by 2031, a cumulative savings that wouldn’t even cover the first year of the proposed program.

For myself, I am pleased that this too long neglected area is getting national attention, and hope that it will engender action and investment. However, I remain skeptical of the immediate (political and economic) feasibility of the broad stroke policy at present. That skepticism is fueled, at least in part, because the program, or at least the political pitch for the program, rests on funds from cost savings elsewhere. There is never a silver bullet in healthcare, much less the financing of healthcare. Long Term Care is expensive, and we are facing a radical challenge in the coming years in caring for aging seniors. That is not something that can be addressed by savings elsewhere, and it is a “soda can” that can’t be kicked down the road indefinitely. While I am skeptical of Harris’s ability, if elected, to push this expanded benefit through Congress in the near term, my hope is that this is an important first step in the campaign to address and fill a critical gap in our health and social service network.